Researcher Spotlight: Dr Justin Pigott

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 17 August 2023

- 0 Comment

My work focuses on the social and religious history of the later Roman empire – in particular its eastern half – and I have a particular interest in the early Church, cities, and domestic slavery. I have been daydreaming about the past for almost as long as I can remember. Having spent my early childhood in Southwest England daydreaming about ancient Romans and medieval knights, it was perhaps only natural that once I started studying history at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, it was the period of late antiquity that quickly became an obsession. One that I am yet to shake!

After completing my MA in Auckland, I took up a PhD scholarship in Australia. My doctoral work examined early Constantinople’s development from a dynastic capital to a new Rome, with a particular focus on the city’s religious evolution and the relationship between the imperial court and bishops. My infatuation with the city of Constantinople – and Byzantine history in general – began many years previously when I had picked up a world history book and opened it at an extract from Nicetas Choniates. In it the historian described the knights of the Fourth Crusade sacking Constantinople and putting a prostitute on the patriarchal throne in Hagia Sophia (Game of Thrones eat your heart out). The book went on to describe the ancient wonders of the city and how its citizens considered themselves Romans. I was both mesmerised and deeply confused. How could I just be learning this now? Why when I was taught Roman history at school was I given the impression that it had all come to an end by the fifth century? I had a lot to learn. My indignation at Byzantium’s lack of visibility grew ever more righteous as I learnt about how it sat at the crux of world religion, how it carried the flame of classical teachings, and how Constantinople remained the urban centre par excellence across Europe.

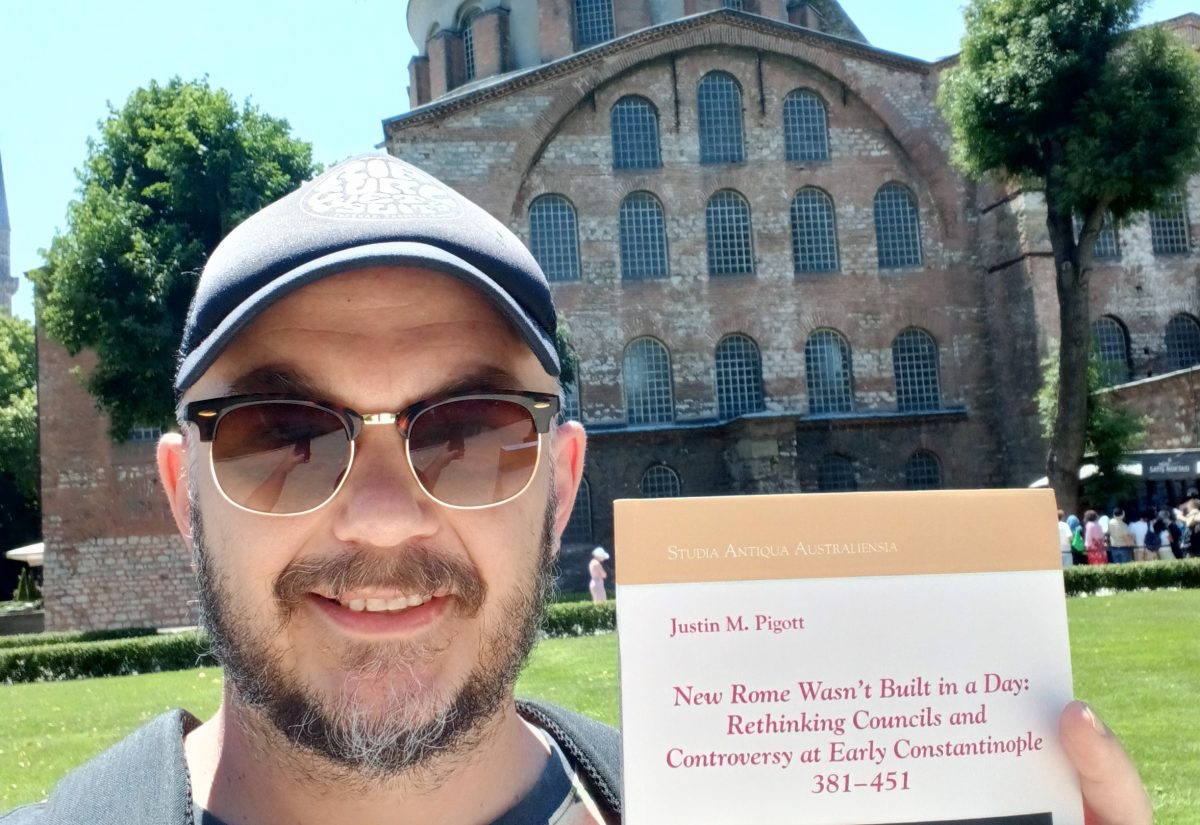

In certain ways this indignation still informs my work, peeling back centuries of historiographical treatment of Byzantium by western European sources opens up rich new ways to understand the Roman-empire-that-never-fell and the societies that lived within and alongside its territories. It certainly formed a large part of my doctoral thesis which was published as a monograph by Brill entitled: New Rome Wasn’t Built in a Day: Rethinking Councils and Controversy at Early Constantinople 381-451. After returning to New Zealand, I took up a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Auckland working on Assoc. Prof. Lisa Bailey’s project: Servants of God, Slaves of the Church: Rhetoric and Realities of Service in Early Medieval Europe. Alongside my post-doctoral research, I also worked as a Professional Teaching Fellow in Classical Studies and Ancient History, teaching undergraduate and postgraduate courses on many topics surrounding the ancient world.

Researching slavery has been a deeply rewarding topic for me and one I am delighted to continue working on. As a social historian it allows you an opportunity to peer into some of the most intimate and ever-present aspects of domestic life. Yet at the same time, slavery is such a pervasive practice throughout ancient and medieval cultures that it also offers a unique way to trace large-scale societal changes. For example, in a recent article on slave ordination (“Heaven-Bound Dung Beetles”, The Journal of Theological Studies) I sought not only to highlight the transition of traditional forms of Greco-Roman slavery into the newly emerging religious worlds of late antiquity but to sketch out the attitudes and experiences of particular slaves and their masters. There is also something deeply satisfying in the effort to shine a light on an enslaved population that whilst making up such a large proportion of the Roman population, have continued to exist in the dark.