DoSSE project members will be presenting at the International Medieval Congress in Leeds, this coming July. Here, we set out what we will be presenting...

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 2 months Ago

- 2 Min Read

Update (21/5/2025): We have filled our spare paper slot – Broderick Haldane-Unwin (University of Oxford) will be presenting on ‘Captivity and Credit: Gregory the Great...

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 2 months Ago

- 3 Min Read

Hosted by the DoSSE project, Niall Ó Súilleabháin (Université de Poitiers) will be giving a public lecture at the University of Leicester on the subject...

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 3 months Ago

- 2 Min Read

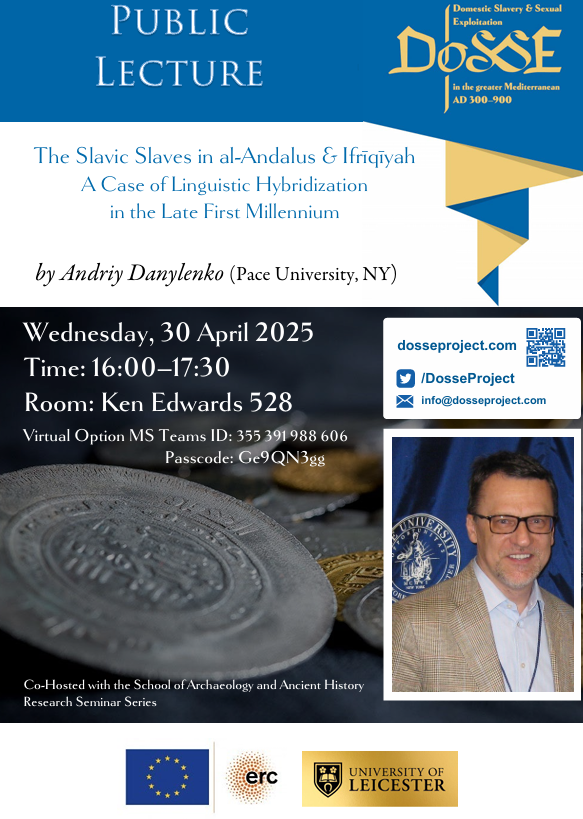

It is with great pleasure that we announce the visit of Andriy Danylenko to the University of Leicester, and his Public Lecture on the subject of: The...

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 3 months Ago

- 4 Min Read

By James R. Burns DID YOU KNOW that Theodoric the Great, ruler of the Ostrogoths (c. 475-526), was the son of two slaves? Well, he...

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 6 months Ago

- 2 Min Read

Apply here: https://jobs.le.ac.uk/vacancies/11322/research-associate-domestic-slavery-in-late-antiquity–2-positions-available.html Vacancy terms: Full-time, fixed term contract for 15 months, or until 30 September 2026, whichever sooner. Salary details: Grade 7 – £39,105...

(Limoges, France, the home of Pelagia.) ‘Since the pressures of the world weighed heavily on a woman, not least on a widow, Erkanfrida needed to...

Last week, I went to the Silk Roads exhibition at the British Museum. It situated slavery in wide-ranging Eurasian commercial networks, through which (for example)...

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 12 months Ago

- 4 Min Read

(James C. Scott, 1936–2024. Photo credit: Yale.) By James Burns Even if one accepts that the serf, the slave, and the untouchable will have trouble...

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 12 months Ago

- 6 Min Read

By Justin Pigott This month some of the DoSSE team made the short trip north to the International Medieval Congress in Leeds. As a historian...