The Life, Work and Death of Child Slaves in the Late Roman World

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 1 September 2025

- 0 Comment

A guest post by Eniko Toth

Editorial note: Eniko Toth has just finished her third-year in Classical Studies at the University of Lincoln. She originally drafted this three-part blog post for the Special Subject, ‘Slavery in the Late Antique World’, run by Professor Jamie Wood. It was selected and edited for publication by Jamie and members of the DoSSE project. You can learn more about the module from Jamie’s guest post [click here!]. If you have any queries or comments about this post, please reach out to Jamie at jwood@lincoln.ac.uk.

I. Commemoration of Child Slaves in the Second and Third Centuries CE

Tombstones can reveal how enslaved people wanted themselves to be memorialised. Roman funerary monuments have survived in large quantities, and a surprising proportion of them relate to freedmen/women due to their increased wealth at their disposal and their desire to demonstrate their newly acquired status (Loven, 2011; Brunn, 2015).

The number of surviving tombstones remind us of the importance for contemporaries of commemorating the memory of a passed loved one (Carroll, 2011). As established in Roman laws, funerary monuments were designed to preserve memory (Carroll, 2006). Tombstones were also an opportunity to display the “public image” and status of an individual (Loven, 2011).

As children were less likely to be commemorated than adults, and slaves less than free/freed people, those instances where they are commemorated gain particular significance (Saller and Shaw, 1984). Funerary monuments allow us to observe many aspects of the short lives that child slaves led, especially their familial relations.

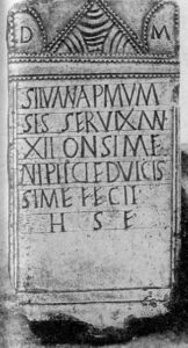

The second century CE tombstone above is dedicated to 12-year-old ‘Silvana, the slave of Publius Mummius Sisenna’, by her grandmother. It is a great example of how tombstones can reflect affection. The fact that the child is enslaved suggests that the grandmother was also still enslaved, especially as it was not unusual for slaves to commission tombstones using money given by owners (Brunn, 2015).

Rather than a family relation, enslaved people are not infrequently found mentioned alongside their owners. If their owner happened to be an elite, wealthy member of the community, then an enslaved child’s relationship to their owner might actually heighten their social standing, even after death (Carroll, 2006). Therefore, Roman funerary monuments often portray aspects of the deceased which emphasise their social status for the onlookers.

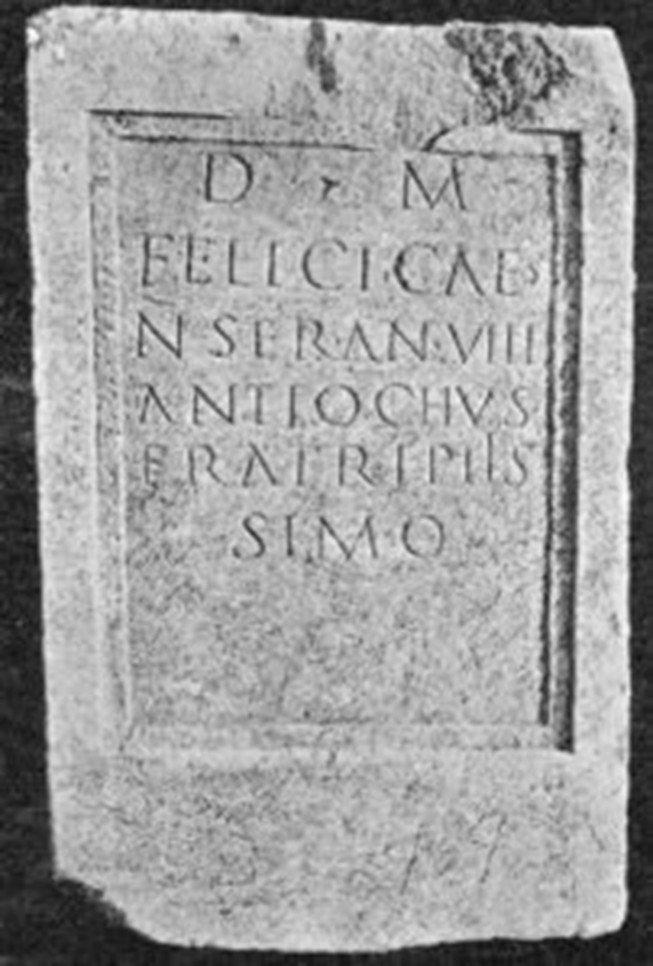

An epitaph to an imperial slave (ILJug-3, 2615), Solin in modern-day Croatia (ancient province of Dalmatia); third century CE.

Similarly, a third-century CE tombstone is dedicated to 8-year-old ‘Felix, the slave of our Caesar’ showcases how slaves enslaved to the imperial family were usually far better off than other enslaved people or even poor freeborn individuals, a fact that was advertised on their tombstones (Carroll, 2006).

Imperial slave owners showcased their wealth through the commemoration of their deceased slaves (Loven, 2011). When compared to the previous tombstone, this one is unusually without adornment. This leads to the suggestion that Antiochus, the commemorator for this tombstone and the brother of Felix, was also a slave. The reference to the imperial household is significant, emphasising the child’s social status.

In summary, the tombstones of both Silvana and Felix speak to the importance of memorialisation in the late antique world and underlines the commemoration that even child slaves could receive. The references that are made to owners were not only important status indicators, but also underline their continuing grip over their enslaved property, even in death.

II. The Work of Child Slaves in the Third and Fourth Centuries

Freeborn Roman children might expect their childhood to involve an education or time spent freely playing with siblings or friends. On the other hand, the childhood of enslaved children was marked by two milestones: the end of infantia and the age of thirty when they could formally be freed (Laes, 2008).

A skeleton from 303-309 CE of a 12.5-year-old male shows the extensive hardships put on the body by intense physical labour. Specifically, there are signs of burdening on the shoulders already, suggesting harsh labour as a ploughman or an oarsman (Laes, 2008). If it is assumed that this skeleton belonged to a slave, then it is clear just how enslaved children were often forced to toil, to their physical detriment.

Seated dancer, late fourth century CE [Silver with gold details]. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (69.72).

Child slaves are often depicted completing rural work, textile work, or as performers within the entertainment industry (Sigmund-Nielsen, 2013; Laes, 2008). Some of these jobs even associate children’s domestic labour with the issue of sexual vulnerability of people enslaved within the home. For example, Columella (On Agriculture 12.4.3) stated that the ‘sexual purity of children makes them fit as kitchen helps’.

Child’s Tunic with Figural Decoration, 5th/6th century Egypt. Brooklyn Museum (26.751). Available here.

Columella’s incorporation of a child’s purity is not the only such example. An Egyptian papyrus from 310 CE portrays the sale of a child into slavery. The contract describes the child as ‘3 years old’ and ‘honey complexioned’. Although this may be in order to distinguish which slave the contract was referring to, it also suggests that close attention was paid to appearance.

The “attractiveness” of slaves was often taken into account by owners, likely leading to a large number of child slaves experiencing sexual exploitation throughout their lifetime. One such source, albeit from an earlier period (the first century CE), is a letter by Seneca, in which he relates seeing his old delicium (young, ‘pet’ slaves) again. Upon seeing Felicio, a former ‘pet slave’ to whom Seneca used to bring ‘little images’, Seneca describes him as a ‘broken-down dotard’ and states that ‘his teeth are just dropping out’ (Seneca, Epistles 12.3). Though there are differences in interpretation, some scholars argue that Seneca’s use of puer delicatus references a previous sexual relationship when Felicio was young (Watson and Watson, 2009). The use of nicknames within childhood, as well as the gifts by Seneca, certainly portray a close relationship between the two.

When connected to the description of appearance in the sale of a slave child above, it becomes clear that owners ascribed significance to the appearance of young household slaves in Late Antiquity.

The Death of Seneca, 1612-1615 [oil on canvas]. Museo Nacional del Prado (P003048).

Moreover, the surprising insults thrown at Felicio due to his age further show that these close relationships were solely a result of the “purity” of young enslaved children. Whilst these “friendships” with owners likely improved the child being freed later in life, this was only possible once they had endured gruesome experiences and the loss of their childhood.

Child slaves certainly led extremely difficult lives, with little protection from exploitation. They were often over-worked from an extremely young are, leaving life-long signs on their body. Even if it improved their chances of future freedom, enslaved children were undoubtedly subject to harrowing lives of sexual exploitation.

III. The Exposure of Infants and the Slave Trade in the Fourth Century CE

Devastating realities gripped young children who were abandoned in the late Roman world (i.e. ‘foundlings’). Although, as Paolella (2020) points out, the early medieval slave trade was carried out via the ‘violence and terror of sudden raids’, when parents needed money quickly they might resort to selling freeborn children. In other cases, such children were abandoned or kidnapped. These cases illustrate how muddled the line between ‘free’ and ‘slave’ really was throughout the fourth century.

Marble portrait head of the Emperor Constantine I. ca. 325-370 CE. [Marble]. At: The Metropolitan Museum, Greek and Roman Art. 26.229.

In 331, Constantine ruled that those who found exposed children ‘shall have the right to keep the said child under the same status as he wished it to have’ (Code Theod. 5.9.1). Constantine’s law, though it did not necessarily have slave traders in mind, ultimately reinforced the legal security of slave traders who acquired abandoned children. This ruling was based on the idea that, through abandonment, the paterfamilias (the head of the household) forfeited his paternal power (patria potestas) over the child as well as his freedom to recover the child in the future (Code Theod. 5.9.1; Monnickendam, 2019).

This law outlines an especially upsetting truth regarding exposed children: from the moment that their parents made their decision, the children were abandoned not only by their own family but by the law. Their freeborn status did not protect them from such exposure or the subsequent hardships that might befall them.

Forlani, P. Mediterranean Sea Region 1569. Library of Congress.

Late antique human trafficking spanned the Mediterranean and Black Seas (Paolella, 2020). Harris (1999) states that exposed infants were the source of 157,933 new slaves a year. Moreover, the fact that Constantine made a ruling could be an indication of the scale at which children were exposed across the Roman world.

The fourth century Christian writer Epiphanius opposed the act of exposure, a belief that was widespread across Christian communities (Monnickendam, 2019). Epiphanius praised those who took in exposed children, without consideration of what that child’s future might hold, describing the parents of the child as having left ‘him to die’ (Ephiphanius, Panarion 66.75.9-10). Yet majority cases of abandonment were a result of ‘suffering from lack of sustenance’, as seen by Constantine’s 323 law which determined that those who were tempted to expose their children ‘shall be assisted through Our fisc before he becomes a prey to calamity’ (Theodosian Code 11.27.2; Monnickendam, 2019).

Another fourth-century Christian writer, Augustine, describes a raid near his city by slave merchants ‘in shrieking mobs’ (Augustine, Letter 10.2) and recounts the story of a girl who the church ‘set free from this wretched captivity’ by ‘slave merchants’ (Augustine, Letter 10.3).

St. Augustine of Hippo, n.d., Catholic Online.

Abductions ‘marked a systematic input’ to the slave supply; in fact, the word ‘kidnapper’ (andrapodistes) is semantically equivalent to the Greek word for ‘slave-trader’ (Harper, 2011; Paolella, 2020). Indeed, literary and legal sources portray the period as a time of terror for children, their parents, and their wider community, reflecting the fact that late antique slavery was built upon a system of enslaving young children with little regard to their status at birth.

Bibliography

Primary sources:

A grandmother commemorates her granddaughter (AE 1978, 201), Brundisium in southern Italy (modern-day Brindisi); second century CE.

An epitaph to an imperial slave (ILJug-3, 2615), Solin in modern-day Croatia (ancient province of Dalmatia); third century CE.

Augustine, Letters in The Works of Saint Augustine: A Translation for the 21st Century trans. by S. J. Roland Teske (New City Press: New York, 2001).

Columella. On Agriculture, Volume III: Books 10-12. On Trees. Translated by E. S. Forster and Edward H. Heffner (1955). Loeb Classical Library 408. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Epiphanius, Panarion in The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis, Books II and III. De Fide trans. by Frank Williams (Brill: Boston, 2013).

Seneca. Epistles, Volume I: Epistles 1-65. Translated by Richard M. Gummere (1917). Loeb Classical Library 75. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

The Theodosian Code in The Corpus of Roman Law (Corpus Juris Romani) trans. by Clyde Pharr (Oxford University Press: London, 1952).

Secondary sources:

Bodnaruk, M. (2022). ‘Late Antique Slavery in Epigraphic Evidence’, in Chris L. de Wet, Maihastina Kahlos and Ville Vuolanto (eds), Slavery in the Late Antique World, 150-700 CE. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brunn, C. and Edmondson, J. (eds) (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carroll, M. (2006) Spirits of the Dead: Roman Funerary Commemoration in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carroll, M. (2011). ‘”The mourning was very good”: Liberations and Liberality in Roman Funerary Commemoration’, in Valerie Hope and Janet Huskinson (eds), Memory and Mourning: Studies on Roman Death. Oxford; Oxbow Books.

Harper, K. (2011). Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275-425. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harris, W. V. (1999). ‘Demography, Geography and the Sources of Roman Slaves’, The Journal of Roman Studies, 89, pp. 62-75.

Hezser, C. (2005). Jewish Slavery in Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Laes, C. (2008). ‘Child Slaves at Work in Roman Antiquity’, Ancient Society 38: 235-283.

Lenski, N. (2023). ‘Slavery in the Roman Empire’ in Damian A. Pargas and Juliane Schiel -(eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Global Slavery throughout History. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham: 87-107. [online] https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13260-5_5 [accessed 5 May 2025].

Loven, L. L. (2011). ‘The Importance of Being Commemorated: Memory, Gender and Social Class on Roman Funerary Monuments’, in Helene Whittaker (ed), In Memoriam: Commemoration, Communal Memory and Gender Values in the Ancient Graeco-Roman World. Cambridge, Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Mohler, S. L. (1940).‘Slave Education in the Roman Empire’, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philology Association 71: 262-280.

Monnickendam, Y. (2019). ‘The Exposed Child: Transplanting Roman Law into Late Antique Jewish and Christian Legal Discourse’, American Journal of Legal History, 59, pp. 1-30.

Paolella, C. (2020). Human Trafficking in Medieval Europe: Slavery, Sexual Exploitation, and Prostitution. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Roth, U. (2021). ‘Speaking Out? Child Sexual Abuse and the Enslaved Voice in the Cena Trimalchionis’, in Deborah Kamen and C. W. Marshall (eds.), Slavery and Sexuality in Classical Antiquity. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press: 211-238.

Saller R. P. and Shaw, B. D. (1984). ‘Tombstones and Roman Family Relations in the Principate: Civilians, Soldiers and Slaves’, The Journal of Roman Studies 74: 124-156.

Sigismund-Nielsen, H. (2013). ‘Slave and Lower-Class Roman Children’, in Judith Evans Grubbs and Tim Parkin (eds). The Oxford Handbook of Childhood and Education in the Classical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 286-301.

Strong, A. K. (2021). ‘Male Slave Rape and Victims’ Agency in Roman Society’, in Deborah Kamen and C. W. Marshall (eds.), Slavery and Sexuality in Classical Antiquity. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press: 174-187.

Watson, P. and Watson L. (2009). ‘Seneca and Felicio: Imagery and Purpose’. The Classical Quarterly 59.1: 212-225.

Images (in order of presentation)

A grandmother commemorates her granddaughter (AE 1978, 201), Brundisium in southern Italy (modern-day Brindisi); second century CE.

An epitaph to an imperial slave (ILJug-3, 2615), Solin in modern-day Croatia (ancient province of Dalmatia); third century CE.

Child’s Tunic with Figural Decoration, 5th/6th century Egypt. Brooklyn Museum (26.751).

Seated dancer, late fourth century CE [Silver with gold details]. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (69.72). Workshop of Peter Paul Rubens, The Death of Seneca, 1612-1615 [oil on canvas]. Museo Nacional del Prado (P003048).

Catholic Online (n.d.) St. Augustine of Hippo. Available from https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=418 [Accessed 4 May 2025].

Forlani, P. Mediterranean Sea Region 1569. Library of Congress. Available https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcwdl.wdl_06765/?r=-0.67,-0.029,2.339,0.669,0 [Accessed 4 May 2025].

Marble portrait head of the Emperor Constantine I. ca. 325-370 CE. [Marble]. At: The Metropolitan Museum, Greek and Roman Art. 26.229.