Teaching Slavery in Late Antiquity – a reflection

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 14 July 2025

- 0 Comment

Guest post by Jamie Wood (University of Lincoln)

In Spring 2025, Jamie Wood (https://staff.lincoln.ac.uk/jwood) ran Slavery in Late Antiquity, a new final-year undergraduate module on the University of Lincoln’s Classical Studies programme, for the first time. The module recruited students from across the School of Humanities and Heritage, some of whom had studied the ancient world throughout their degrees and some who were entirely new to it (or hadn’t studied it since secondary school, or even earlier). The module drew on work that he had done as part of his Leverhulme Trust International Fellowship, The Unnamed , which looked at the role of enslaved people in the Christian church in the Iberian Peninsula in Late Antiquity (fifth to seventh century). In the following post, Jamie reflects on the module and introduces the student work that we’ll be publishing over the next couple of months.

***************

I’ve learnt so much about slavery and other things during the fellowship. This wasn’t particularly difficult as it wasn’t a topic that I’d engaged with in much detail beforehand. Over the past year or so, I’ve given a bunch of papers, and will be publishing the results of the research in the coming years.

Today I want to tell you about the module that I devised as part of the fellowship. In the funding bid, I said that I’d teach the students with what I’d learnt during the fellowship. While I certainly shared some of my findings with them, in the end I learnt much more than I would have done if I’d not run the module.

Adopting, as far as possible, a ‘life cycle’ approach to studying enslaved people in Late Antiquity, we began by considering the question of where the enslaved originated from (e.g. slave trade, natural reproduction), moving through childhood to work, family life, households, manumission, death and commemoration.

My project focuses on the roles of people – especially enslaved individuals – who are not named by our sources. During the module, we got particularly interested in the representations of enslaved people in visual culture, in which they often appear as background figures in the activities of social elites. I’d not really thought about the fact that these enslaved figures aren’t named until I began discussing them with the students.

The Projecta Casket. Produced ca. 380 CE in Rome. The decoration suggests that it was a toilet casket given as a wedding present. It combines mythological scenes and the Christian inscription: ‘Secundus and Projecta, live in Christ’. Source: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1866-1229-1?selectedImageId=36295001

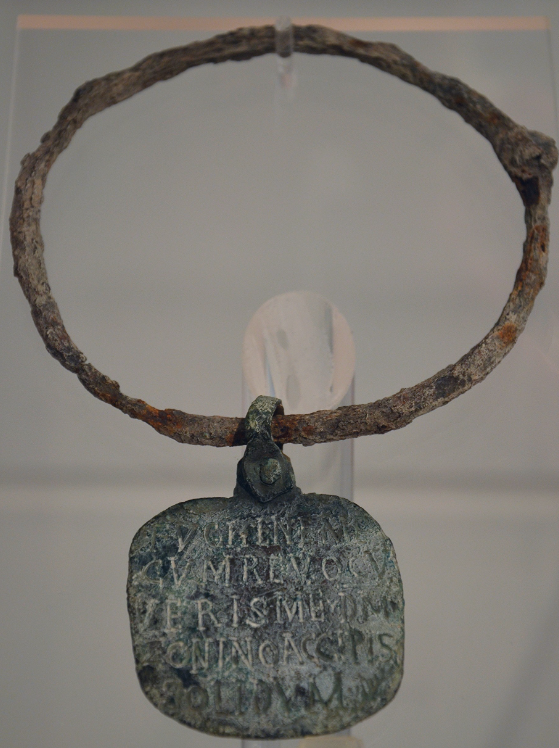

We also thought about the lack of direct material evidence for enslaved people in Late Antiquity, a curious fact given that enslaved people played a pivotal role in the physical making of that world. Students found the phenomenon of slave collars (https://daily.jstor.org/slave-collars-in-ancient-rome/) interesting, especially the ways in which these objects, which speak directly to the physical brutality of slavery, appropriate the voices of (unnamed) enslaved people.

Slave-collar found in Rome with a bronze disc announcing the reward for returning the runaway slave to his or her master, Zoninus, 4th-6th century CE, National Museum of Rome, Baths of Diocletian, Rome (source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/carolemage/30079358246/in/photostream/)

Our interest in material and visual culture was also driven by the fact that I assessed the students by asking them to write a series of interlinked blog posts. And, as we all know, blogs work better if they include some images! I had to train the students how to write blogs, especially encouraging them to consider their audience, to develop skills in writing in different (non-academic) registers and to think about how their work looks. Rather than writing for me and maybe a second marker, they had to think about how they would communicate what they have learnt with an online audience.

The DoSSE project team kindly suggested we might give the students the opportunity to publish their blogs, which we’ll be doing over the coming weeks and beyond. Before you read the student blogs, I wanted to offer a reflection on what we all took away from the module. In addition to writing three 500-word blog posts, I asked the students to produce a 500-word reflection on their experience, so that gives me a reasonable idea of how the module might affect what they do or think in future. It was also a good way to get them to practice writing reflectively.

While some students felt that the blog assessment was challenging and unfamiliar, nearly all of them said that they appreciated having the opportunity to write for an audience that extended beyond the module tutor and felt that it had positively impacted their writing skills. They liked the interactive PowerPoints that I used to structure seminars and to enable them to share the results of their collaborations and discussions, with several saying that they had used these when writing their blogs.

Several commented on how what they had learnt in the course of the module had made them think differently about the ancient world, about slavery, and even about labour relations in the modern world.

For example, drawing on scholars such as Candida Moss, we discussed the idea of ‘hidden labour’ – who did the physical work that made late antique society, who took the credit, and who got recognized for its achievements by posterity. A few students commented not only that this changed how they thought about late antique society and the vital roles played by subordinate people, but also about whose contributions are recognized and valued nowadays.

Candida Moss, God’s Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible (London: Harper Collins, 2024) (link)

Another student commented to me that their prior studies had left them with the impression that ancient slavery ‘wasn’t that bad’ and that most slaves were manumitted after a few years. By the end of the module, they were able appreciate the violence of the social and economic relationships out of which slavery was constructed, how their excesses were mitigated infrequently and grudgingly (and usually only because it served the interests of the enslavers), and about how those slaves we know about are a vanishingly small proportion of the total.

As I reflect a couple of months after the module finished, I am fairly confident that the quality of student work was much higher than I’d normally expect. Having students produce three blog posts on an overarching topic resulted in a greater intensity of engagement with the scholarship and – especially – the sources. Although some students felt that the 500-word limit per blog meant that they hadn’t been able to go into as much depth as they would have liked, in my view their prose was more direct and less waffly than usual (there was certainly much less of what I describe as ‘filler’). The requirement that they integrate images resulted in a more rounded and visually engaging final product. Finally, the reflections were a really effective way of helping students to recognise skills that they have gained and to think about what they have learnt on a module, rather than leaving it implicit.

The students’ posts deal with topics as diverse as female and child slaves, depictions of the labour of the enslaved on Roman artwork, sexual exploitation of the unfree, and a fictionalised account of the life of a Carpian slave.

I hope that readers will engage with these blog posts on their own terms – as undergraduate student-authored texts that are intended to be engaging for a general audience. I appreciate that there may be some errors and would ask anyone who finds any to reach out to me. I will do my best to have the posts updated. Any queries or suggestions about developing the module can similarly be directed to me (jwood@lincoln.ac.uk).

This work was supported by a Leverhulme Trust International Fellowship, which has involved spending time at the Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies (https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en) and the Centro de Estudos Clásicos at the Universidade de Lisboa (https://centroclassicos.letras.ulisboa.pt/). Find out more about the overall project here: https://makingdigitalhistory.co.uk/network/the-unnamed-slavery-and-the-making-of-the-church-in-late-antique-iberia/

The DoSSE project is a 60-month research project, funded through a grant from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 101001429).