Female Slavery in the Third and Fourth Centuries CE

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 10 September 2025

- 0 Comment

A guest post by Molly Dumbrell.

Find out how enslaved girls were exploited in Late Antiquity; what their domestic burden was; and if manumission really meant freedom for female slaves…

Editorial note: Molly Dumbrell has just finished her third-year in Classical Studies at the University of Lincoln. She originally drafted this three-part blog post for the Special Subject, ‘Slavery in the Late Antique World’, run by Professor Jamie Wood. It was selected and edited for publication by Jamie and members of the DoSSE project. You can learn more about the module from Jamie’s guest post [click here!]. If you have any queries or comments about this post, please reach out to Jamie at jwood@lincoln.ac.uk.

1. The Exploitation of Enslaved Girls

Slavery was an important part of everyday life in Roman society. Enslaved people lived across the Empire and had a significant impact on social and economic practices. Young girls were a part of this. By exploring objects from the past, we can paint a picture of what slavery was like for enslaved girls in Late Antiquity.

There were many ways that someone could become a slave. These included birth into slavery, capture in war, self-enslavement and infant abandonment (Harper, 2011). Enslaved children were regularly moved from household to household and even town to town (Pudsey and Vuolanto, 2022). Girls were at a higher risk of being subjected to child exposure (abandonment, often in a public or semi-public space), with many found, reared and then sold on. Papyri from late antique Egypt show that many girls who were sold into slavery were fifteen or younger. Some girls were as young as three years old (Laes, 2008).

‘I acknowledge that I have sold to you from now in perpetuity the female slave that I own [Name], who is at present 3 years old, honey-complexioned, at the price agreed between us of …ty [i.e. 30-90] talents of silver coin, which I have received in hand in full here, in return for which [she will remain with you and] you will have control and ownership of the purchased goods and the right to supervise and manage her however you like’ (Source: Bodleian Papyrus 1.44)

This papyri from 310 CE is a receipt of the sale of a slave girl in Egypt. The source features a description of the slave, to show the buyer that the slave is good quality. This shows that very young children were sold into slavery across the Empire. Many of these slave contracts were adapted from contracts for the sale of farm animals, as can be seen in the use of transactional language (Parkin and Pomeroy, 2007), demonstrating how enslaved people were property and an ordinary aspect of business transactions.

Another papyrus from the third century CE highlights the sale of a ‘Moorish’ girl as a slave. This document shows the highly organised sale of the girl, listing a large number of individuals present in the process. This document highlights the complexity of legal frameworks for selling slaves in this period.

P.Oxy. L 3593. Instructions to a Rhodian Bank about Sale of a Slave Girl.

From these sources, we can see that papyri are essential for understanding the enslavement of young girls. Most surviving sources were produced from the viewpoint of the male elite and are skewed towards their social and political views. This makes it even more important to learn about the origins of enslaved girls.

Once young girls were sold into slavery, they were put to work as soon as possible, including in many cases hard labour. For example, in rural areas, girls would act as shepherds as soon as they were out of infancy (Sigismund-Nielsen, 2013). Young slaves would receive training in order to boost their efficiency and increase their value. Human remains have been found that show the signs of the hard labour that these girls were expected to complete (Laes, 2008).

Young girls in Late Antiquity were enslaved in a variety of ways. They were exploited from a young age and seen as property. The sources discussed here show the complexity of the slave trade across the Empire and the harsh conditions that enslaved young girls experienced.

2. The Domestic Burden of Female Slaves

Female slaves played an essential domestic role. Their individual roles were shaped by their specific skillsets. Some female slaves would have undertaken unskilled labour which involved the general upkeep of the household (Hezser, 2005). Others would have completed specialised tasks such as nursing, entertainment and sex work. The household was a unit of production and consumption, making the role of female slaves significant to its efficiency (Hezser, 2005; Harper, 2011). Slaves did most of the general domestic work within the household, which would not have functioned without their labour (Lenski, 2023).

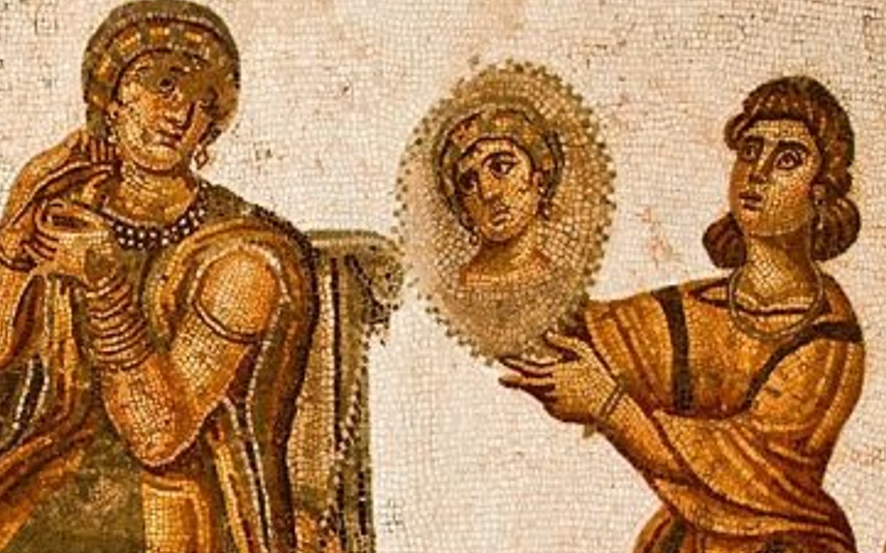

Roman mosaic showing a woman in the morning toilet, surrounded by servants. Object dated to the 4th century CE. The object comes from the Sidi Ghrib Baths in Tunisia. It is now in the Bardo Museum, Tunis.

This mosaic from fourth century CE Tunisia highlights the domestic labour that female slaves may have undertaken for their owners. In the image, two female slaves are attending to their mistress. The slave on the right is holding up a mirror and the slave on the left is offering a plate to the mistress, who is sitting (Rose, 2008). The slaves depicted in the image would have been charged with maintaining the adornments and other possessions of their mistress. They are dressed so as to differentiate them from their mistress (Rose, 2008).

The mosaic would have been commissioned by an elite owner for their home as a sign of their wealth demonstrating that they were able to buy slaves and to put them to work domestically (Rio, 2017). Compositionally, it also emphasises the centrality of the elite woman in the middle rather than the slaves (Rose, 2008).

The following from a letter of the fourth century CE Roman writer and politician Symmachus offers an idealised vision of his daughter overseeing slave labour within the household.

‘My lady daughter, I rejoice to be honoured with the rich memento of your wool-working: it displays both your love for your father and your industry as a married woman. Women in the old days are said to have led their lives like this…sitting or walking among the wool weighed out for your slave-girls and the threads which mark their daily weaving, you think that these are the sole delights of your sex.’ (Source: Symmachus, Letters 6.67 – late 4th century, trans. Gillian Clark)

This source, produced from the perspective of the elite (like the mosaic examined above), highlights the value of skilled labour in the household, particularly textile work.

Women were essential to textile production in late antique households (Rio, 2017; Kelley, 2023). Spinning, weaving and mending clothes were important elements of domestic production and from a young age female slaves would have been trained to complete this skilled work. The involvement of female slaves in textile production further underlines the diverse nature of female enslaved labour – both skilled and unskilled – in the household.

3. Manumission: Were Female Slaves Really Freed?

Manumission was the formal process of freeing slaves. It was an important economic process with social implications (Mouritsen, 2016). Freedom was granted to freed slaves, allowing them to own some property and earn money. There was a variety of reasons for the manumission of female slaves. Sources regarding manumission include laws, wills and estate surveys (Harper, 2011). However, not all recorded manumissions meant full freedom from a female slave’s former master.

Manumission may have occurred as a reward for loyalty, long service or as a gesture of affection (Perry, 2014). The process acted as an incentive for slaves to work harder. Female slaves were more likely to be manumitted due to personal relationships with their owners, although this was often the result of sexual exploitation. A female slave’s usefulness – and in many cases her chances of manumission – was based upon her ability to produce children, who would inherit her status as slaves of the master (Perry, 2014). Female slaves were unlikely to have been manumitted until they could no longer give birth to more slave children – i.e. until they were no longer reproductively active.

Two formal modes of manumission applied to female slaves. Manumissio vindicta required the owner to manumit in front of a magistrate. Manumissio testamento allowed slave owners to provide freedom for their slaves in their will (Perry, 2014). Both modes gave female slaves full freedom as well as Roman citizenship, with rights nearly equal to those of freeborn women. It was also specified when the slave was manumitted that she also received a peculium, a small amount of property (Koops, 2020).

The following papyrus document, dated to the early third century CE, records the will of Psenamounis Harpocrates, who arranged for the manumission of a 13-year-old slave girl upon his death:

‘The will of Psenamounis Harpocrates, son of Harpocrates, mother Thatres from the city of Oxyrhynchus. Literate. Psenamounis makes his son Aurelius Theodorus, the child of his now deceased wife Diogenis from the same city, his heir. Immediately on his death he frees Damais, his slave girl, who is approximately 13 years old and releases her from her obligations to her patron and grants her all her peculium. He also bequeaths to her control a quarter of the servant’s accommodation that he possesses in the same city in the quarter of the theatre of Plataea along with all the household items and at the same time a bed with a mattress on top. This is on condition that she may not rent this out, except to the extent that she may rent it to my brother if she wishes.’ (Source: Papiri greci e latini (PSI) 9.1040, 216/7 CE)

In this source the slave girl is granted her freedom via manumissio vindicta. She is also released from any obligations to her patron, given a peculium and living quarters with goods. Unlike some other slaves, the girl was granted autonomy from a patron. This source may illustrate a more benevolent relationship between some owners and their slaves. It also shows that manumission could happen at any age and not just for those who have been enslaved for a long time.

Freedom though usually did not mean autonomy. Most freedwomen were still bound to their former owners, who remained her patron, a relationship that was compulsory (Harper, 2011). Such patrons retained legal authority over their former slaves, including expectations of loyalty and service. A freed slave still owed operae – work established by contract (Harper, 2011). In most cases, therefore, the bond between patron and freed slave grew stronger through their legal obligation to each other (Rio, 2017).

In summary, although after manumission, some freedwomen could build a life for themselves, ensuring the stability of their household and their children, the vast majority were bound legally, financially and socially to their former owner and current patron – not all freed slaves were truly free.

Bibliography

Primary sources

Bodleian Papyrus 1.44.

Papiri Greci e Latini (PSI) 9.1040.

P.Oxy. L 3593.

Roman mosaic showing a woman in the morning toilet, surrounded by servants. 4th century CE. Bardo Museum, Tunis.

Symmachus, Letters 6.67, trans. Gillian Clark.

Secondary sources

Harper, K. (2011). Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275-425. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kelley, A. (2023). ‘Searching for Professional Women in the Mid to Late Roman Textile Industry’, Past & Present, 258.1, pp. 3-43.

Koops, E. (2020). ‘The Practice of Manumission through Negotiated Conditions in Imperial Rome’, in G. Dari-Mattiacci and D. P. Kehoe (eds.) Roman Law and Economics: Volume II: Exchange, Ownership, and Disputes, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 35-78.

Laes, C. (2008). ‘Child Slaves at Work in Roman Antiquity’, Ancient Society, 38, pp. 235-283.

Lenski, N. (2023). ‘Slavery in Ancient Rome’ in D. Pargas and J. Schiel (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Global Slavery throughout History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 87-108.

Mouritsen, H. (2016). ‘Manumission’, in P. J. du Plessis, C. Ando and K. Tuori (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Roman Law and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 402-416.

Parkin, T. and Pomeroy, A. (2007). Roman Social History. New York: Routledge.

Perry, M. J. (2014). Gender, Manumission, and the Roman Freedwoman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pudsey, A. and Vuolanto, V. (2022). ‘Enslaved Children in Roman Egypt: Experiences from the Papyri’, in C. L. de Wet, M. Kahlos, and V. Vuolanto (eds.), Slavery in the Late Antique World, 150–700 CE. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 210–223.

Rio, A. (2017). Slavery after Rome 500-1100. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rose, M. (2008). ‘The Construction of Mistress and Slave Relationships in Late Antique Art’, Woman’s Art Journal, 29.2, pp. 41-49.

Sigismund-Nielsen, H. (2013). ‘Slave and Lower-Class Roman Children’ in J. Evans and T. Parkin (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Childhood and Education in the Classical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 286-301.