A Slave, Her Mistress, and a Donkey’s Deadly Penis

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 23 August 2023

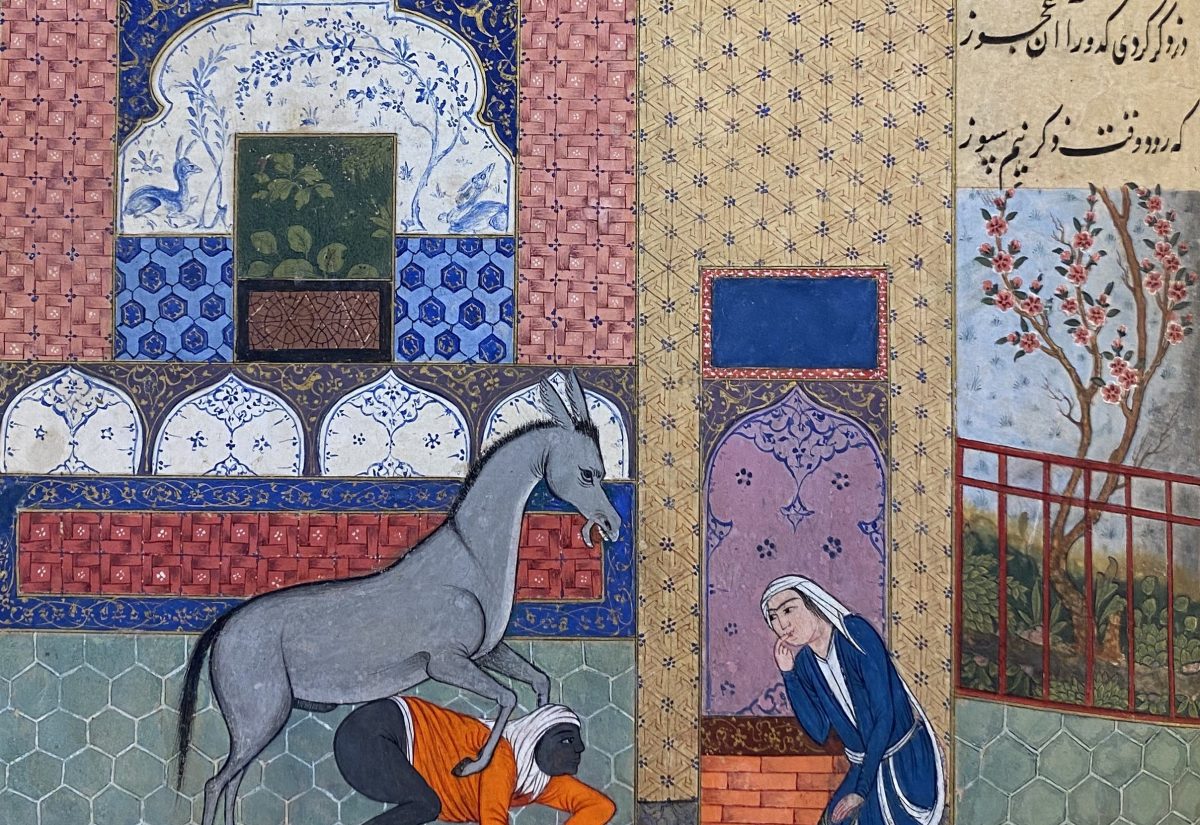

![]() Photo Credit: British Library Add. MS 27263, f. 298r

Photo Credit: British Library Add. MS 27263, f. 298r

There is a story in Masnavi-i Ma’navi, written by Rumi, the famous poet, mystic, and scholar from thirteenth-century Persianate world, about a female slave and her mistress—both slave and mistress are unnamed, referred to simply as Kinīzak (female slave) and Khātūn (noblewoman). And there is also a donkey. To put it short, the story goes like this: there was a slave who used to have sex with her mistress’s donkey. She had taught the animal how to perform like a man. To reduce the risk of penetration, and to prevent him from going too far, she had her own trick: she would use a gourd.

As time passed, the donkey started to become lean and as thin as a hair. The mistress helplessly wondered why. She showed the donkey to horseshoers and got no answer. So she tried to solve the riddle on her own. During her investigation, she saw a shocking scene through a crack in the door: her slave was under the donkey, just as a woman lying with a man. She became jealous, and thought to herself: ‘How is this possible? I have a greater right to this donkey. After all, it is my property! It seems that the donkey has been perfectly trained for this, like a set table with a burning lamp, inviting me!’

Pretending she hadn’t seen anything, she knocked at the door and called the slave, saying: ‘O Kinīzak, how much more you want to sweep the room?’ Of course, she said this simply to announce her presence. The slave quickly hid the gourd, grabbed a broom, and opened the door. She made her face unhappy and pretended to be fasting, telling her mistress she was busy cleaning the room. The mistress looked at the donkey that was half-finished, its penis still moving, but feigned ignorance. She told her slave to put on her veil, and she dispatched her on an errand, just to get rid of her.

The mistress closed the door behind her. Very happy and excited, she thanked God for a moment alone with this donkey. She started to imitate what the slave had done, laying beneath the donkey and raising her legs. The donkey penetrated her as it was trained, but since there was no gourd, it burst her liver and tore apart her intestines. The mistress died, and the whole courtyard was smeared with blood. ‘Such a bad ending’, wrote Rumi, ‘Have you ever seen a martyr to a donkey’s penis?’

When the slave returns to find her mistress dead, she sighs and declares: ‘O Khātūn, you sent the expert away and foolishly risked your life! O stupid Khātun, the teacher showed you a beautiful picture, yet you only saw the appearance and didn’t learn its secret. You saw the penis, but didn’t see the gourd. Or you were so distracted by the love of the donkey that the pumpkin remained hidden from your eyes.’

Rumi, as is his style in his Masnavī, attempts to discuss higher truths by recounting mundane stories and anecdotes. He presented the story of Kinīzak and the donkey as an allegory to demonstrate that enthusiasm is no substitute for expertise, and that every deficient insight and understanding is accursed. In one beyt, he compares imperfect knowledge with how some ignorant people, drawn to the spiritual benefits of Sufism, see only the ṣūf, or the woollen mantle, worn by holy men, and not the skill and expertise required to understand their spiritual path.

There are two points to make about the slave in this very interesting story. Firstly, her function in the allegory. The moral of the story can be summarized in this way: a seeker of knowledge who does not endeavour to acquire this knowledge properly, and to ask a master for insight, will be misled and arrive only at a defective and dangerous level of understanding. Thus, the seeker of knowledge is the mistress; the ecstatic apprehension of knowledge is the sex pleasure offered by the donkey; the defect in the knowledge is the absence of the gourd. And, of course, the spiritual master here is the slave, who calls herself ustād, which translates as ‘expert’. Let’s not forget that, in Sufism, the spiritual master has a great role in guiding the seeker on his path to the truth and unity with God. Undoubtedly, Rumi relied on the irony and juxtaposition of a slave as an expert and master to give his point a greater impact.

Secondly, although in terms of the power dynamic, it may seem radically progressive to see a slave who is inferior in its essence as an expert, let’s not forget her area of expertise, which is having sex with a beast. This is something that she tries to hide, by pretending to be as her mistress would expect her to be, completely inferior and in a lower position, with tears in her eyes and a broom in her hands, working hard obediently while she is fasting.

Sheida Heydarishovir

*This story has been fully translated into English by Reynold A. Nicholson, in his book “The Mathnawi of Jalalu’din Rumi”.

For accessing full translation of Masnavi online: http://www.masnavi.net

Comments are closed.

That was a thought-provoking story. It reminded us of the importance of seeking true expertise and not being deceived by appearances.

Thank you for sharing this with us.