A Comedy Tonight: The Querulous Master & Totally Evil Slave

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 30 October 2025

- 0 Comment

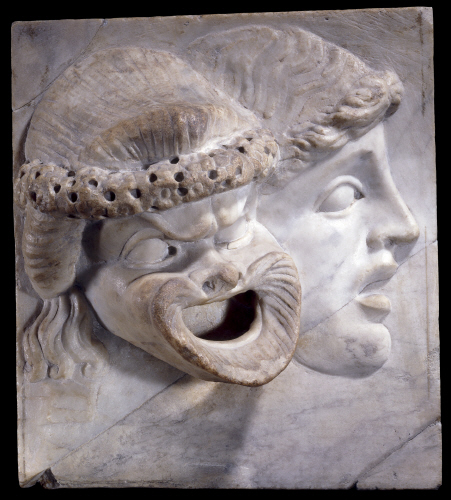

(Relief showing Roman comic theatre masks. © The Trustees of the British Museum.)

By James R. Burns

The DoSSE project team is working on a sourcebook for late antique slavery, featuring Latin, Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, Syriac, and Persian texts, and more. This post showcases one of the sources we’ll include: the Late Roman comedy known as the ‘Querolus’.

IT IS AGREED AND MOST EVIDENT THAT ALL MASTERS ARE EVIL. Truly, I am expert enough: none is worse than mine. Certainly, he is not a dangerous man, but rather too ungrateful and rotten. If a theft has been committed in the home, it is execrated as some wicked crime. If he sees something being ruined, he continuously shouts and curses, how evil! If anyone knocks a chair, table, or bed into the fire, as customarily happens in our haste, he even complains about this. If the roofs leak, if the doors are broken, he calls all of us to him, seeks all of us. By Hercules! This is unbearable. Moreover, all the expenses and accounts, he writes with his own hand. Whatever payment is not shown to him, he demands to be restored.[1]

So begins the speech of a slave character Pantomalus about his owner, Querolus, the title character of a Latin, Late Roman comedy (the only extant one from Late Antiquity). His rant will soon escalate into pure salaciousness…

But, first, some brief historical context. The Querolus is thought to have been written in early fifth-century Gaul. But the author is unknown and much about its origins are uncertain. We do not know if the Querolus was ever performed, but its survival in medieval manuscripts means that the text was read and copied in the early Middle Ages.

Pantomalus is an example of the ‘clever slave’, a well-established stock character of Roman comedy. Such characters, and the comedic setting as a whole, allowed sentiments that might seem subversive to be voiced in a light-hearted manner. Despite the problems posed by the provenance and genre of the Querolus, it allows some insight into the real-life anxieties of owners and slaves, as Kyle Harper and others have discussed.[2]

Both Pantomalus and Querolus have exaggerated personas. The former’s name literally translates as ‘all evil’ (Greek panta + the Latin malus), and the latter’s as ‘complaining’ (querolus). Querolus is depicted as being excessively neurotic. They cannot be seen as representations of typical masters and slaves.

Yet the script also shows that it was entirely possible for people to conceive of resentment among slaves against their own owners and owners generally. The anxieties that Pantomalus attributes to Querolus are fairly mundane and probably would have been recognisable to real-life slaveholders: they concern theft of goods; failure to maintain the home; and annoying accidents.

Moreover, the humour of Pantomalus’s speech comes from how he is anxious over Querolus’s anxieties because the latter is right: Pantomalus and his fellow slaves do look for ways to cheat him. For example:

Now I cannot think there is anyone alive who might be able to so placate his perverse customs. What’s more, he constantly realises when wine has been tainted and diluted with water. We are also in the habit of mixing different wines together.[3]

Such ‘everyday’ acts of non-compliance – or ‘resistance’, if one follows James C. Scott’s interpretation [4] – may well have been more common sources of anxiety for slaveholders than the possibility slaves might run away or violently strike back (two acts which risked even greater danger for the enslaved).

Yet, states Pantomalus, for all Querolus’s anxieties, he does not even begin to suspect what slaves really get up to…

However, we are not as wretched and as stupid as certain people suppose. Some believe us to be sleepy, seeing that we nod off during the day. Yet we do this as a result of our vigils, for we are awake during the nights. The slave [famulus] who rests during the daytime hours is awake during the time for sleeping. I reckon nothing better was ever made by nature in human affairs than night. Night is our day, when all things are done. We visit the baths by night, though it is tempting during the day. Moreover, we bathe with attendants and slave girls [puellae], is this not the free life? Indeed, being adorned with just enough light or brightness so as to suffice, we are not discovered. I hold naked her whom the master is scarcely allowed to see clothed. I inspect flanks, I divide folds of hair, I lay down, I embrace, I caress, I am caressed. Which of the masters is allowed to do this?[5]

Although this section could reflect the fears of slaveholders over what might happen when they are not looking, Pantomalus’s speech has descended into an obscene fantasy. Indeed, the question posed at the end might have had an ironic edge for a contemporary audience, given the routine sexual exploitation by male owners of their female slaves (if it is right to assume that the woman mentioned as enslaved). The character of Pantomalus was but an instrument for the play’s free, probably elite male author.[6] The vivid account it gives of him fondling the body of the woman might even be interpreted as a pornographic indulgence of the libido of slaveholders.

Overall, then, the Querolus shows how the anxieties of owners and slaves might be imagined and justified – but also exaggerated, perverted, and ultimately laughed away.

Translation and commentary by James R. Burns. We intend for an extended version to appear in the sourcebook.

[1] Omnes quidem dominos malos esse constat et manifestissimum. Verum satis sum expertus nihil esse deterius meo. Non quidem periculosus ille est homo, verum ingratus nimium et rancidus. Furtum si admissum domi fuerit, execratur tamquam aliquod scelus. Si destrui aliquid videat, continuo clamat at maledicit, quam male. Sedile mensam lectum si aliquis in ignem iniciat, festinatio nostra, ut solet, etiam hinc queritur. Tecta si percolent, si confringantur fores, omnia ad se revocat, omnia requirit, hercle hic non potest ferri. Expensas autem rationesque totas propria perscribit manu. Quidquid expensum non docetur, postulat reddi sibi.

[2] Kyle Harper, Slavery in the late Roman world, AD 275–435 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 249–252.

[3] Iam excogitare nequeo quid sit, quod tam pravis placere possit moribus. Vinum autem corruptum tenuatumque lymphis continuo intellegit. Solemus etiam vinum vino admiscere.

[4] James C. Scott, Weapons of the weak: everyday forms of peasant resistance (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1985), pp. xv–xvi, 34.

[5] Et non sumus tamen tam miseri atque tam stulti quam quidam putant. Aliqui somnulentos nos esse credunt, quoniam somniculamur de die; nos autem id facimus vigiliarum causa vigilamus noctibus. Famulus qui diurnis quiescit horis, somni vigilat tempore. Nihil umquam melius in rebus humanis fecisse naturam quam noctem puto. Illa est dies nostra, tunc aguntur omnia. Nocte balneas adimus, quamuis sollicitet dies. Lauamus autem cum pedisequis et puellis, nonne haec est vita libera? Luminis autem vel splendoris illud subornatur, quod sufficiat, non quid publicet. Ego nudam teneo quam domino vestitam vix videre licet. Ego latera lustro, ego effusa capillorum metior volumina, adsideo amplector foveo foveor. Cuinam dominorum hoc licet? Illud autem nostrae felicitatis caput, quod inter nos zelotypi non sumus.

[6] Though the possibility that the author was a former slave is not altogether impossible – the Roman playwright Terence seems to have been a freed slave.

Bibliography

Brandenburg, Y., Aulularia sive Querolus (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2023).

Harper, Kyle, Slavery in the late Roman world, AD 275–435 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Mathisen, Ralph, People, personal expression, and social relations in Late Antiquity, 2 vols. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003).

O’Donnell, Rosemary Dorothy (ed. and trans.), The ‘Querolus’, vol. 1/2, doctoral thesis (University of London, 1980).

Scott, James C., Weapons of the weak: everyday forms of peasant resistance (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1985).