Sanctioning Sexual Exploitation

- Erin Thomas Dailey

- 20 August 2025

- 0 Comment

Guest post by Lauren Pugsley

Editorial note: Lauren Pugsley has just finished her third-year in Classical Studies at the University of Lincoln. She originally drafted this blog post for the Special Subject, ‘Slavery in the Late Antique World’, run by Professor Jamie Wood. It was selected and edited for publication by Jamie and members of the DoSSE project. You can learn more about the module from Jamie’s guest post [click here!]. If you have any queries or comments about this post, please reach out to Jamie at jwood@lincoln.ac.uk.

Sexual violence and slavery were deeply entwined in Late Antiquity, with slaves of both sexes facing exploitation from childhood. The issue was so widespread that third-century Roman author Lactantius condemned the abandonment of children lest they be sold into prostitution. For men this exploitation usually ended after entering adulthood; however, mature women continued to face constant abuse, vulnerable to the desires of elite men and demands of their mistresses.

Image Credit: Le temple d’Apollon à Bulla Regia :https://archive.org/details/letempledapollon01merl/page/n18/mode/1up?ref=ol

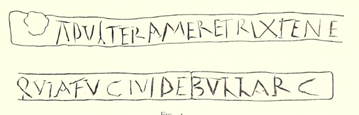

Freeborn citizens were indifferent to the suffering of female slaves, with some considering sexual services part of their contribution to a household: in this view, enslaved women had a duty to provide both a personal service and to bear the next generation of slaves, following their masters’ advances. According to Paolella (2020), ‘society assumed women’s sexual exploitation’, with the exploitation becoming ‘institutionalised’. Our evidence seems to agree with this statement, with elite women employing their female slaves to perform sexual acts on their behalf—most likely those the wife found unappealing or degrading. Demands of this kind suggest owners viewed slaves as little more than tools to be utilised rather than autonomous beings with opinions and preferences. This is seen most clearly in the discovery of a fourth-century slave collar in Bulla Regia, Tunisia. The collar, pictured above, was found alongside a woman aged around forty and reads ‘I am a filthy/slutty prostitute; retain me; I have fled from Bulla Regia’.

The inscription would have been clearly visible, publicly shaming and humiliating the woman, dehumanising her as lost property, and emphasising her status solely as an object of pleasure for her master. The woman’s age is especially poignant, as it suggests she spent majority of her life in sexual captivity, even past the prime age to conceive. Similar collars have been found that can be dated to Late Antiquity (sometimes discovered alongside skeletal remains), with women valued primarily for their sexual potential, and owners having the right to use them sexually without legal restriction.

Queen Hecuba’s speech in Seneca’s first-century play Trojan Women emphasises this right of owners when she commands her subjects to expose their breasts in preparation for the Greek men who will soon claim them as war slaves:

‘Let our group make ready, its shoulders stripped: drop your clothes, tuck in their folds, bare your bodies down to the womb’ (Speech of Hecuba from Seneca, Trojan Women 87-89)

Already, before having met her enslavers, Hecuba assumes she will be exposed to sexual exploitation, and she appears resigned to her fate. This acceptance of violence provides further insight into female slaves’ lack of autonomy; they had no option but to suffer the maltreatment, retraining their bodies to be constantly exposed to men. Additionally, we see the implication that elite women perpetuated this maltreatment, allowing their husbands and male kin to abuse domestic slaves, with no moral obligation felt towards the victims.

Hecuba also reveals societal views towards female war captives. The very fact of their enslavement made them sexually dishonoured. Their impurity and defilement were assumed from the point of their capture or sale, and they were therefore unable to achieve a reputation on par with the elite wives of the men by whom they were exploited—a view echoed in the dehumanising Bulla Regia collar. This idea was widespread, impeding women’s chances to escape servitude, or to live unimpeded by sexual coercion and its consequences even if she did achieve freedom.

It is abundantly clear that female slaves were viewed as little more than readily available property to be sexually exploited, with enslavers facing no social sanctions for their actions.

Sexual exploitation of female slaves was normalised in Late Antiquity, with women dehumanised and used according to their owners’ whims. This institution of exploitation was validated by legislation and moral teachings, which encouraged men to abuse enslaved women by treating them as a no-consequences alternative to sex with free women—who were protected under adultery laws.

Justinian’s sixth-century legal code emphasises this, punishing men who ‘ravished’ free women, while permitting the rape of dishonourable women, including actors, prostitutes and slaves, who had no legal recourse (Ward, 2022).

‘Anyone who has ravished a free woman, or one who is married, shall be punished with death’ (Justinian, Digest 48.6)

The threat of death to those who abused ‘honourable’ women reflects the idea that the enslaved did not deserve respect, with the master granted sexual access to his slaves as a legal right (Harper, 2011). Fifth-century Christian teachings also enabled this behaviour even though they considered it sinful, with Paulinus of Pella excusing his younger self for sexually exploiting the slaves of his household, on the grounds that it enabled him to avoid the crime of adultery with ‘free-born loves’. Here we see moral principles ultimately serving to facilitate the sexual exploitation of the enslaved, with relationships with free women (other than procreative sex within marriage) deemed immoral and an insult to both the woman and her family’s honour, while slave women continued to be regarded as lacking sexual honour.

Furthermore, the use of enslaved women as replacements for free women is highlighted by their links to prostitution, with the terms used almost interchangeably: both were referred to as available for public use, while many prostitutes were purchased at slave markets. Patterson (2012) claims that the prostitution of women was profitable, providing a source of livelihood for slave holders; significantly, these profits could be increased by the kidnapping of freeborn girls into enslavement. Poor girls from rural areas were easily tricked with the promise of new clothes and an improved life within large cities; once within the city, however, they were isolated from their male kin (who could have enacted legal recourse against the slave holder) and coerced into signing legally enforceable contracts of sexual slavery (Paolella, 2020). Alongside the kidnapping of girls, poor families would sell their children into slavery, especially women who were viewed as a burden on the family. Both the kidnapping and selling of freeborn children into slavery were so widespread by the late fourth and early fifth centuries that emperors Theodosius II and Valentinian introduced legal restrictions on the trading of children, showing legal attempts to reduce exploitation of female slaves (Codex Justinianus 1.4.12).

Despite the legislative efforts in the fifth century, exploitation continued, forcing Emperor Justinian to conduct an enquiry into prostitution in 530 AD, leading to the outlawing of enslavement of exposed children and the legal freeing of numerous girls in brothels by empress Theodora, as described by chronicler John Malalas:

‘The pious empress returned the money and freed the girls from the yoke of their wretched slavery’ (Malalas, Chronographia 18.24)

Alongside the freeing of the girls, Theodora granted them money, preventing them from being immediately recaptured into slavery, and ordered the barring of brothel keepers. These actions can easily lead us to believe sexual exploitation of female slaves was practically outlawed by this period; however, this was not the case, as legislation focused on offering protection to freeborn women who had been coerced into slavery. This meant war slaves, or those born to slaves still had no legal protection and were instead forced to submit to the whims of free men.

But women could use sexual relationships to their advantage, by gaining manumission in return for good service, through the production of children, by becoming a concubine, and through marriage to their former master.

There is evidence of female slaves being freed by owners for marriage from the classical period, with men forming mutual relationships with a single slave whom they then freed in order to marry. This is clearly shown in the funerary relief depicting Lucius Antistius Sarculo and his wife and freedwoman Antistia Plutia (Lucius’ former slave):

The British Museum: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1858-0819-2

The relief clearly evidences women being freed by their masters for the sole purpose of marriage, and in the case of Antistia, some level of mutual love was likely present, implied by the ornate carvings and recognition of Lucius’ good deeds below the portraits. Furthermore, Justinian permitted men to marry their manumitted slaves, regardless of status—a limitation imposed by previous legislation—which allowed a greater number of women to achieve freedom through this method (Bagnall,1995). Unfortunately, with these increased opportunities came further restrictions on the autonomy of women, who were virtually unable to unilaterally divorce their husbands, and likely still suffering sexual exploitation even following manumission. Similarly, a woman could be manumitted as a reward for successfully fulfilling her ‘womanly duties’, implied to be sexual favours. She might be valued above other slaves and may be more likely to be freed, akin to men being manumitted for generating high profits (Witcher, 2024).

Alongside marriage, women could also achieve manumission through reproduction; according to first-century author, Columella, if a woman produced several sons, she would be granted exemption from work, and if she birthed more, she could achieve freedom.

‘For to a mother of three sons exemption from work was granted; to a mother of more her freedom as well’ (Columella, On Agriculture 1.8.20)

Here we see the importance of women for the continued reproduction of slaves, with fertile female slaves valued for their ability to continually produce additional labour for households. Any children born would follow their mother’s status, providing labour to be inherited by future generations. Significantly, however, women existed at the whims of their owners, as there was no legal obligation to free slaves following reproduction. A woman could potentially be continually raped by her owner and produce (illegitimate) offspring until she was no longer of fertile age. There is evidence of women remaining in sexual servitude to their masters even following the exchange of children, with a second century inscription describing how Zopura, a slave woman, sold her children to a slaveholder in return for her freedom; however, she was still required to live with him until his death, likely as his unmarried sexual partner (Marshall & Kamen, 2021).

Bibliography

Primary sources

Funerary relief, British Museum [online] (1858,0819.2) image: relief; funerary equipment | British Museum (accessed 7 May 2025).

John Malalas. Chronographia 18.24, trans. by Elizabeth Jeffreys, Michael Jeffreys, and Roger Scott (Melbourne: Australian Association for Byzantine Studies, 1986).

Justinian, Digest, [online] Codex of Justinian: Liber I (accessed 6 May, 2025).

Lactantius, Divine Institutes Book 6.20 trans. by William Fletcher (Buffalo: Christian Literature Publishing Co, 1886).

Lendering, Jona. Bulla Regia Slave Collar, reads (‘adultera meretrix tene quia fugivi de Bulla Regia’) digital photograph, Musee du Bardo, Tunisia [online] Accessed 02 March 2025,<Bulla Regia, Slave collar – Livius>

Lucius Columella, On Agriculture trans by. Harrison Boyd Ash (Cambridge, MA; Harvard University Press, 2006) 1.8.20.

Paulinus of Pella, Eucharisticus 165 trans. by Hugh G.Evelyn-White (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1921).

Seneca, Trojan Women, trans. By John G.Fitch. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018), Loeb Classical Library.

Secondary sources

Bagnall, Roger. ‘Women, Law and Social Realities in Late Antiquity: A Review Article’, The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 32.1(1995): 65-86.

Glancy, Jennifer. Corporal Knowledge: Early Christian Bodies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Harper, Kyle. Slavery in the Late Roman World AD 275-425, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Kamen, Deborah. Marshall, C.W. Slavery and Sexuality in Classical Antiquity (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2021).

Karras, Ruth Mazo. ‘Injection: A Gender Perspective on Domestic Slavery’, in The Palgrave Handbook of Global Slavery Throughout History, ed. By Damian A Pargas and Juliane Schiel (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), pp. 215-227.

Merlin, Alfred. Le Temple d’Apollon à Bulla Regia, (Paris: Paris, E. Leroux, 1908).

Paolella, Christopher. Human Trafficking in Medieval Europe: Slavery, Sexual Exploitation, and Prostitution (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020).

Patterson, Orlando. ‘Trafficking, Gender and Slavery: Past and Present’, in The Legal Understanding of Slavery: From the Historical to the Contemporary, ed. By Jean Allain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 322-359.

Ward, Ian. ‘Ovid’s Casebook: The Literary Jurisprudence of the Metamorphoses’, New England Classical Journal 49.2 (2022): 13-31.

Witcher, Thomas. ‘Breaking Bondage: Manumission and the Absence of Abolitionist Ideology in Rome’, Chancellor’s Honours Program Projects (2024). [online] https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/2573