Guest post by Ellie Sadler

Editorial note: Ellie Sadler has just finished her third-year in Classical Studies at the University of Lincoln. She originally drafted this three-part blog post for the Special Subject, ‘Slavery in the Late Antique World’, run by Professor Jamie Wood. It was selected and edited for publication by Jamie and members of the DoSSE project. You can learn more about the module from Jamie’s guest post [click here!]. If you have any queries or comments about this post, please reach out to Jamie at jwood@lincoln.ac.uk.

I. How Roman Art Eternalised the Labour of the Enslaved

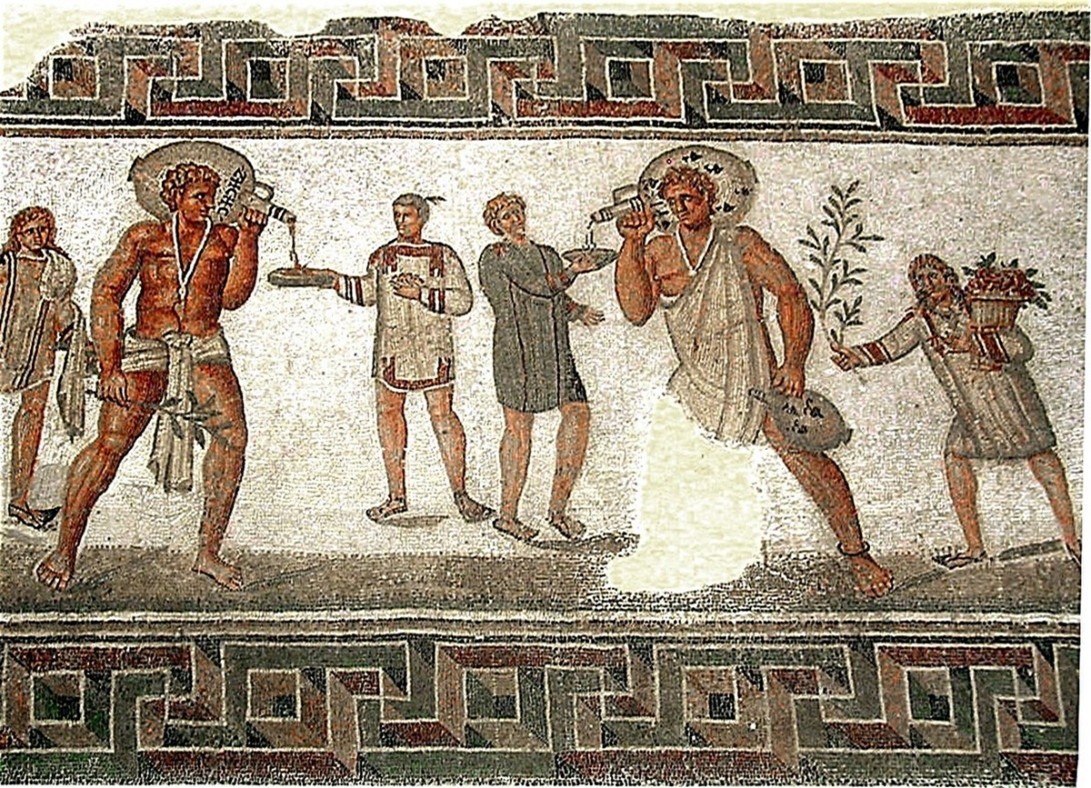

Slavery was a defining institution of the Roman world. It was embedded in economic and social life. Historical accounts detail the lives of the enslaved. Artwork provides unique visual evidence of their roles. The third-century Mosaic of the Cupbearers [pictured above], found in Dougga but now displayed in the Bardo National Museum, Tunisia, is one such example.

Glimpses into Roman Slavery Through Art

This mosaic portrays male attendants serving at a banquet. They are carrying large amphorae of wine and wearing simple tunics. The inscriptions (Greek words rendered in Latin letters) “PIE” (DRINK!) and “ZHCHC” (YOU WILL LIVE) suggest an active scene. Behind the joyous atmosphere, however, lies the sharp reality: these men were enslaved. Their service is proof of the strict hierarchy of Roman society.

💡Did you know? Roman banquet scenes often featured enslaved attendants to highlight the status of their masters, rather than the individual person (Bradley, 1994). 💡

Hidden Messages in the Mosaic

⭐AMULETS FOR PROTECTION

The enslaved men are shown wearing protective amulets, mostly used to ward off misfortune. This could suggest that even within their restrictive conditions, slaves found ways to protect themselves from harm (George, 2013) and could suggest that personal belief systems continued despite oppression, although it is equally possible that the amulets were placed on the slaves by their owners to protect their human possessions.

⭐SCALE OF FIGURES

Typically, in Roman art the size of figures matters. Larger individuals – owners – were the focus of the art, while the slaves were smaller and in the background (George, 2013), which makes this artwork exceptional as the slaves are much larger than the elites and clearly the focal point. This prominence may suggest an important role for enslaved workers in elite households, specifically in the context of hosting and serving, which was central to Roman social life.

⭐EVER-PRESENT REALITY OF SLAVERY

Slavery was ingrained into the visual culture of Roman daily life. This mosaic was originally displayed in the reception or dining area of a villa in Dougga, North Africa. This was a public space that was used to entertain guests. The mosaic normalises the presence of enslaved workers within everyday life. Artworks like these reinforce the subordinate role of slaves in Roman society (Harper, 2011). The placement of the mosaic, where guests were entertained, enabled the elite to present their wealth and control over slaves as part of their social identity.

Language of Command: Scripted Speech and Symbolic Control

In the Mosaic of the Cupbearers, two inscriptions written in Latin letters stand out:

- “PIE” : Greek for Drink!

- “ZHCHC” : Greek for You will live!

It is clear that these inscriptions do not record conversations. They are commands and will not have been commands given to fellow elites. They will have been directed at the enslaved servants.

ENSLAVED VOICES…NOT IN THEIR WORDS

The mosaic has the two servants in the middle of the action. While it may be assumed that the words are theirs, spoken to the guests, the words are still not their own, because the words are:

- SCRIPTED – Part of a performance and therefore not a real dialogue.

- GENERIC – No names and no personal speech are ascribed to a specific individual.

So, while the mosaic shows the slaves as the focus of the art, they have no voice. Their presence creates the scene for the artwork, but their identity is suppressed.

WHY GREEK?

Greek was used among the elite in the western Mediterranean and it implied that they were highly educated (Bradley, 1994). Many of the enslaved, especially those who worked within the household, were expected to speak Greek. This mosaic shows how language was adapted to serve the elite (Adams, 2003).

THE BIGGER PICTURE

Embedding the commands resulted in a dual functionality:

- Normalising Power – the commands that the slaves copy show that they are extensions of the master.

- Cementing Control – Even the speech used at a dinner party has become a power structure.

Elite Romans preferred to be around Greek speaking slaves in roles such as hospitality and teaching children (Bradley, 1994).

II. Behind the Drapes: Gendered Slavery and Domestic Power in Roman Art

This mosaic takes us into the private life of the Roman elite. This artwork shows three enslaved women caring for a couple in their bedroom. Unlike the previous male mosaic, there is no inscription to identify them. Their only function was to serve.

Visibility without Identity

The female figures were to perform vital tasks such as making the bed, pouring water, and serving. They are essential to the mosaic, yet they have no individuality.

💡While male slaves were associated with public performance and speeches, female slaves were depicted as caring, restrained, and quietly labouring in domestic spaces (Joshel, 1992). 💡

Gendered Space, Gendered Slavery

There is barely any mention in Roman legal materials of enslaved women’s names. The exceptions are for those women who were sold or punished (Bradley, 1994). In elite households, women were expected to partake in emotional and physical labour without autonomy (Levin-Richardson, 2024). The lack of records about women makes this mosaic and others like it so important to understand the lives of enslaved women.

“Women in slavery lived lives of hyper-visibility and invisibility-always seen, never acknowledged” (Huemoeller, 2023)

Enslaved women were often used in intimate domestic places, such as kitchens and bedrooms (Huemoeller, 2023). The placement of the mosaic, in the dining space, supports the point that women were present but played minor roles.

Beyond the Curtain: Visual and Social Barriers

Something that appears to be a decorative curtain in the mosaic, is, in fact, much more than decoration. The curtain is symbolic. Drapery was common in Roman art as it symbolised power and privacy. In this mosaic, it divides the elites from the enslaved women who serve them. It visually enforces hierarchy.

SYMBOLIC THRESHOLDS:

The artwork of Pompeii also depicted enslaved women behind doorways, furniture, or otherwise in the shadows. They were framed, but not central (Hallet, 2008). Their marginalisation in the artwork directly reflects their social and legal marginalisation in Roman life.

HIDDEN LANGUAGE:

The curtain is a code. It tells the audience the rules of the household. Enslaved women were part of the structure of Roman life, yet, as this artwork shows, they were always at one remove, even in spaces that only functioned because of their presence.

III. Born to Serve: What Roman Art Reveals about Enslaved Childhoods

Pompeii, Villa of the Mysteries, fresco 60-40 BCE

This fresco, from the Villa of Mysteries in Pompeii, shows a naked boy intently reading something. Seemingly, a sweet moment of a child learning, the image, known as The Naked Reader, reveals important features of child slavery in elite Roman households (Beckmann, 2023).

Art as Evidence

This style of fresco was very common. Roman wall paintings often featured a small, unclothed child. It has been suggested that this image represented family life. Yet it has also been argued that such artwork reflects the everyday reality of enslaved children: present but vulnerable (Beckmann, 2023).

💡Did you know? Nudity in Roman art wasn’t just about aesthetics. It was used to signify powerlessness, especially in children. 💡

Not A Free Child, A Slave

The young boy in the fresco might have been a verna, a child born into slavery within the household. The boy’s role could have been that of a reader or an entertainer. The nakedness, together with his posture, suggests passiveness rather than agency.

Scholars have argued that scenes such as these suggest that Romans eroticised vulnerability as a way to enforce dominance over slaves (Beckmann, 2023).

Decorated Exploitation

Frescos were not just to decorate the houses. They were used as statements of status and control. The inclusion of children in idealised images of domestic life was a way for elites to normalise the exploitation of children as slaves.

This is supported by the Enslaved Childhoods project, which has shown that children were purposefully displayed in artwork but were left voiceless, reflecting their lack of literary and legal power (University of Edinburgh, 2023).

Why it Matters

This fresco is a clear example that beautiful art can disguise reality. The child in this fresco is presented as learning, shown as a symbol. The child, however, is in fact a symbol of how the elites embedded their power within culture itself.

By displaying enslaved children in domestic art, Roman elites sanitised exploitation as a mere commonplace of day life. A comparison with records from Roman Egypt indicates that such children were essential to the functioning of the household—economically and socially.

By analysing this artwork, we are challenging how visual culture has been used throughout history to mask inequalities and normalise slavery.

Bibliography

Primary sources

3rd Century, Mosaic from Dougga, Tunisia Bardo National Museum, File:Mosaique echansons Bardo.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

3rd Century, Mosaic from Vienna, Austria, Kunsthistorisches Special Episode – Enslaved Women During Slave Revolts with Assistant Professor Katharine Huemoeller – The Partial Historians – Ancient Roman History with smart ladies

60-40 BCE, Fresco from Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii The Naked Reader: Child Enslavement in the Villa of the Mysteries Fresco | January 2023 (127.1) | American Journal of Archaeology

Secondary Sources

Adams, J. N. 2003. Bilingualism and the Latin Language (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Beckmann, Sarah E. 2023. ‘The Naked Reader: Child Enslavement in the Villa of the Mysteries Fresco’, American Journal of Archaeology, 127.1: 55–83

Bradley, K. (1994). Slavery and Society at Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University of Press).

George, M. (2013). Roman Slavery and the Visual Representation of Servitude (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Hallett, Judith P. (2013). ‘Intersections of Gender and Genre: Sexualizing the Puella in Roman Comedy, Lyric and Elegy’, EuGeStA, 3: 195-208.

Harper, K. (2011). Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275-425 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Huemoeller, Katharine (2023), in ‘Special Episode – Enslaved Women during Slave Revolts with Assistant Professor Katharine Huemoeller’, The Partial Historians. Online at: https://partialhistorians.com/2023/01/05/special-episode-enslaved-women-during-slave-revolts-with-assistant-professor-katharine-huemoeller/

Joshel, Sandra R. (1993). Work, Identity, and Legal Status at Rome: A Study of the Occupational Inscriptions (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press)

Levin-Richardson, Sarah (2024). ‘Emotional Labour in Antiquity: The Case of Roman Prostitution’, in Kim Bowes and Miko Flohr, Valuing labour in Greco-Roman antiquity (Leiden: Brill), 109-130.

University of Edinburgh (2024). ‘Enslaved Childhoods: Redefining Roman Slavery’. Online at: https://hca.ed.ac.uk/classics/research/research-projects/enslaved-childhoods-redefining-roman-slavery

Jamie Wood’s research, which he drew upon for the module, was supported by a Leverhulme Trust International Fellowship that involved spending time at the Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Studies (https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en) and the Centro de Estudos Clásicos at the Universidade de Lisboa (https://centroclassicos.letras.ulisboa.pt/). Find out more about the overall project here: https://makingdigitalhistory.co.uk/network/the-unnamed-slavery-and-the-making-of-the-church-in-late-antique-iberia/